From Small Town to Bustling City

In the first half of the 19th century, Saint John underwent a dramatic transformation from a small town in 1800 to a bustling urban centre by mid-century. Seaborne commerce quickly became the mainstay of the local economy. Fish, furs, masts for the Royal Navy, livestock, grains and other foodstuffs were traded, and shipbuilding began.

The geographic location of the city, with the Saint John River providing a highway from the New Brunswick hinterland, placed Saint John in an advantageous position to profit from the timber trade. The development of New Brunswick timber resources during the Napoleonic Wars contributed to Saint John’s growth into a major port with important shipping interests. This was especially true during the War of 1812 when the United States entered the fracas. Saint John declared itself a free port and workers handled tens of thousands of tons of smuggled American goods.

This prosperity brought many changes to the city: houses, wharves and stores were built in great quantities, rents increased and wages were high due to a shortage of labour. This did two things for the city - it supported the timber trade as a mainstay of the economy, and it attracted immigrants from the British Isles.

Sydney Street

A Strong & Diverse Economy

After 1815 the city’s economy began to diversify with business concerns other than those directly connected with the timber trade, emerging as important employers and commodity producers. “The timber trade remained important, but it was increasingly challenged by shipbuilding, construction, sawmilling, and a variety of small crafts and trades.” In short, Saint John was transformed from a mercantile town to a commercial city. Saint John merchants used a combination of financial institutions, transportation links, resource exploitation, and urban development to facilitate transatlantic trade and dominate a hinterland extending for 200 miles around the city.

Saint John was a major immigrant port, processing newcomers at the immigration centre on Prince William Street. Sick mariners and some immigrants were processed at the Partridge

Island quarantine station during the 19th and 20th centuries. These immigrants brought new talents and trades, ideas and capital, but they also brought disease. Epidemics during the 19th and 20th centuries killed hundreds of mariners, immigrants and city residents.

The city experienced many social changes during the 1840s and 1850s, including the incorporation of gas lighting; the installation of a public water supply from Lily Lake, the first in North America; improved sanitation conditions; and the construction of a bridge at the Reversing Falls Rapids. Rockwood Park, one of Canada’s largest urban parks, was developed by the end of the century. The shipbuilding industry continued to grow, with Saint John eventually becoming known as the Liverpool of America.

A Thriving Shipbuilding Centre

Saint John was the third largest shipbuilding centre in the world. The shipyards around the harbour and in the neighbouring communities such as St. Martins launched an average of two ships every week. By mid-century, Saint John played a prominent role in an Atlantic communications system extending to Liverpool and London in one direction, and Boston and New York in the other. In 1874, the city's shipping tonnage was greater than that of the Kingdom of Denmark, nearly three times as great as that of Portugal, and seven times as great as Turkey. Saint John had $12 million worth of shipping afloat, and the import-export trade was worth another $12 million (about $350 million in 2023).

Of the 6,000 wood ships built in New Brunswick during the 19th century, only one remains. That is the ship, Egeria, was built in Millidgeville in 1859. The ship is now part of a wharf structure at Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

MV Happy Rider at Long Wharf

Architectural Development

A further indication of the state of the economy was the architectural development of the city. Saint John's architecture is a direct reflection of its economic development. An article concerning Saint John’s architecture, published in the Daily Telegraph in the 1850s, stated that “utility moreso than ornament determined a building’s style and form and that a city may go on with such structures for a half century or more without anyone endeavouring to break its monotony by the erection of structures of a more tasteful character.”

The writer of this newspaper article then credited the construction of the Commercial Palace (1855) with bringing “to an end the erection of inferior buildings in the principal streets.” It seems possible that the building of the Commercial Palace influenced the erection of domestic architecture; prior to this event there were few homes in Saint John that had “the slightest pretension to elegance or agricultural [sic] beauty.”

The move to brick construction appears to have begun in the early 1850s when “the times have an improving appearance, when we see handsome and substantial Brick Buildings taking the place of old wooden ones.” Old wooden buildings were demolished, or

extensively renovated to present a more favourable appearance. Brick exteriors were added to some wood structures. Undoubtedly this change in direction for domestic architecture was tied to the return to economic prosperity for the city in the 1850’s. This was the period of a building boom in Saint John, as evidenced by the following account in the Morning News:

Notwithstanding the complaint of dull times,

there never were so many buildings being

put up in all parts of this City as at the

present time. We believe that there are

not less than two hundred new structures

and old ones undergoing repairs.

At about the same time, on a tour of Saint John, the editor of the Boston Gazette was a bit more blunt in his comments. “Neither the public nor private buildings, with the exception of the Victoria Hotel, claim much merit for architecture …” He continued to write that the “arrangements and convenience were illustrative of the citizens; dignified without pretence and substantial without pride or show.”

The Great Fire of 1877

These newer more beautiful buildings did not last long. On June 20, 1877, Saint John was revisited by another Great Fires. Fire erupted at Henry Fairweather’s storehouse at York Point and burned out of control for nine hours, destroying the business and residential heart of the central peninsula and the uptown. Over 13,000 people were left homeless, 21 were killed, and the property damage was $28 million, with less than 25 per cent covered by insurance. In 2023 currency that $28 million would be valued at over $750 million.

This fire could well have meant the doom of Saint John were it not for the determination and spirit of the citizens, and the generosity of communities from all over North America and Great Britain. Relief came as cash, food, clothing and building materials arrived from Chicago, Boston, Halifax, Sussex, Ottawa, Glasgow and other communities. Architects, engineers, masons, carpenters and labourers came from all over the continent to aid in the rebuilding of the city.

The prophecy that “from these very ashes and ruins a brighter, a more glorious and more prosperous city will arise” came true, for within five years the city was completely rebuilt.

Within days, work had commenced on hundreds of substantial stone and brick buildings, which came to occupy the fire-ravaged areas. Saint John residents expressed their “good taste” in a manner not done before, by the incorporation of elaborate wood and stone carvings on the building exteriors. Over 60 per cent of the city was rebuilt in wood.

King Street fire

A Population Boom & Prosperous Port

In the 1880s and 1890s, Saint John’s industrial capital, employment, and industrial output increased. In 1882, P.R. Edictor, in an address to the Ladies Society of the Congregational Church, speculated that in 50 years’ time Saint John would have a population of 468,000 people. He said that various carrying lines would be inaugurated to transport people to and from work and places of leisure. There would be a rapid-transit double-tracked elevated railway skirting the south end and the one harbour ferry would be expanded to three. He also predicted that “rum and intemperance have now for many years been unknown evils, and the jail is the most rickety, unused building in the city, while the police are getting rich in peaceful avocations.”

The city rested its economic hopes on continuing prosperity on the port. Over the next 20-plus years harbour facilities improved and were expanded. A description of port activities noted that “the waterfront was not a pretty place, but it was busy, where ships from all over the world came to load and unload in the winter port … [and the] Saint John longshoremen were more honest than those anywhere else, and more efficient.”

Peace-time port activity was supplemented during the First World War when the port assumed a major military role. As the major industrial centre in the Maritimes, and an ice-free port, ships carried munitions, food, horses, machinery, and troops overseas. Over 25,000 New Brunswick men flocked to the recruiting stations to “fight for the Empire.” At home, women were fuelled by the spark of patriotism and replaced men in the factories. The first Canadian killed during this war was Captain Ernest Rae Jones of Saint John, who died in August 1914 while serving with the British Army.

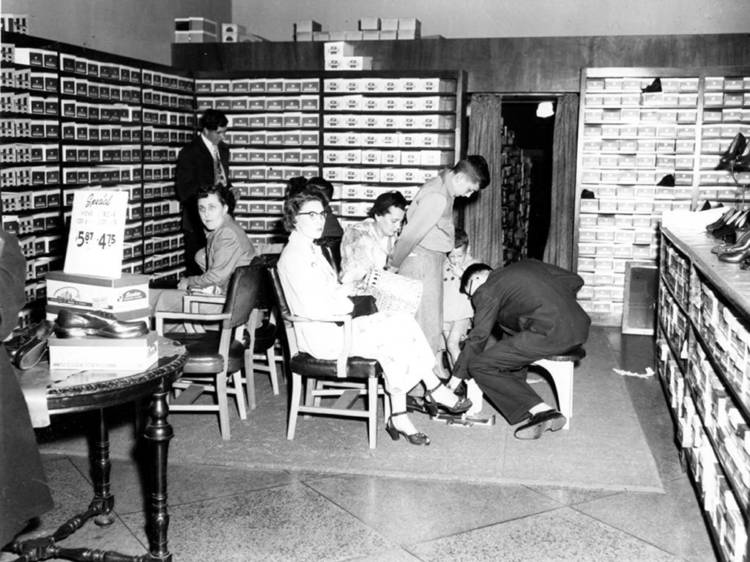

MRA Shoe Department

Wartime Threats & Opportunities

The end of the war brought economic hardships to the city coupled with the disastrous effects of the depression of the 1930s. The city was again on the brink of economic disaster. In 1927 the city sold the harbour facilities to the federal government, and not a moment too soon. In 1931 most of the west side dock facility burned. Quick federal aid to rebuild the port saved the city’s economy. Another federal relief project was the construction of the municipal airport in Millidgeville. Saint John could now service national and international customers by land, sea, and air. The recently constructed drydock allowed the city to compete nationally for ship repair and construction projects.

The outbreak of the Second World War brought economic prosperity, but also the threat of attack from a European enemy. Fear of German submarine and air attack was so great that several forts were established at Mispec, Negro Town Point, Courtenay Bay Breakwater, Fort Howe and Partridge Island. The financial benefits generated by the war greatly overshadowed this threat of attack and the effects of this wartime prosperity continued into the 1950s and 1960s.

King’s Square cenotaph

A Growing City

There were many changes in the physical appearance of Saint John during this time. Veterans housing was built in the Rifle Range and Portland Place, and suburbs emerged in Forest Hills, Champlain Heights and Millidgeville. The Fairview Plaza opened, featuring the Dominion Store, Sobeys and Simpson Sears, as did the Lancaster Mall. The oil refinery opened. A massive urban renewal program replaced slum housing and tenements on Main Street and the surraounding areas, and in the east end. These wooden buildings were replaced by concrete office buildings, highways, landscaped areas, and shopping malls. In 1968, the look of the harbour was forever changed when the Saint John Harbour Bridge was finally built, a 100-year dream. This was then followed by the throughway which encouraged residents to move to the Kennebecasis Valley, and tourists to drive to Saint John.

The 1970’s was the end of an era for many familiar landmarks. The old City Hall on Prince William Street closed as the municipal government moved into a new City Hall. The old Kirk in Carleton was

destroyed by fire. The General Hospital was replaced by the Saint John Regional Hospital. The new viaduct was replaced by a newer viaduct. Union Station was closed, demolished and later replaced by Harbour Station (now TD Station). MRA’s department store and the Royal Hotel were closed and demolished for the Brunswick Square complex. Simonds and Millidgeville North high schools were finished construction, as well as the Brunterm container terminal at the port, and the Point Lepreau nuclear power station. Parkway and Prince Edward Square Malls were constructed. The Bricklin automobile came and went.

By late in the century, the physical landscape of the city had been irreversibly changed. Retail development moved east to McAllister Place, Walmart and Costco in the first two decades of the 21st century. The oil refinery and pulp mill continued to respond to changing worldwide environmental and economic realities. The Port of Saint John saw a resurgence with increased rail traffic and container business and west side facilities expansions.

Saint John Today

Today there is new housing built in all parts of the city. The former Coast Guard base is being redeveloped into the Fundy Quay. The 1980s Market Slip development was re-purposed for new public uses including an outdoor skating rink. A revitalized New Brunswick Museum was announced for the Douglas Avenue neighbourhood.

To quote from the 1877 Great Fire prophecy “a more glorious and more prosperous city will arise” remains true for Saint John’s future.

The City Market